Autumnal changes bring the release of seeds as part of the botanical cycle of life to propagate and sustain new growth each spring. One popular type of seed is a so-called “helicopter” or “whirlybird” seed, which arises from maple and several other tree species. While these pods do contain a seed, they are more accurately identified as samara – a single seed surrounded by a wing and classified as a type of fruit1. The seeds inside the wing are edible and can be roasted, boiled, or dried and ground into flour. The dry, papery wing allows the fruits to utilize fall winds to travel much further from their parent tree than a typical seed pod.

X-Ray Microscopic Imaging – Sample Preparation Options for Challenging Samples

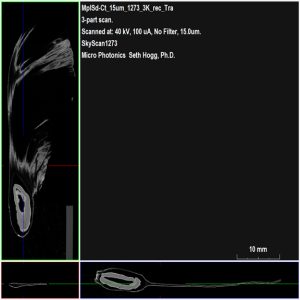

While low density samples are typically straightforward to image using micro-CT, some samples, such as a maple samara, attenuate X-ray energy so minimally that acquiring a usable dataset can be challenging. In this article, we first imaged a recovered seed with no pretreatment to demonstrate the challenges in collecting a dataset for very-low density materials. Next, we collected three more datasets, each with its own unique sample preparation or pre-treatment step aimed at improving contrast between the samara and air in our reconstructed datasets. Each dataset was acquired using our SkyScan 1273 at an isotropic voxel size of 15 µm set to the minimum recommended X-ray energy of 40 kV and only 100 uA of current (4 Watts).

As shown from Bruker DataViewer in Figure 2, the seed within the tip of the samara is well resolved at the 15 µm voxel size utilizing the SkyScan 1273. However, the winged structures are nearly invisible when balancing the dynamic range of our image to account for the local density of the seed. To attempt to create a usable model of this seed structure for computational dynamics would be problematic as we do not have enough contrast between the papery wing signal and background air.

One fast way to boost X-ray attenuation for thin samples where there’s not much internal volumetric information to be captured is to utilize a thin coating of an X-ray dense material. For this project, we utilized deodorant spray containing aluminum to cover the exterior surfaces of the maple samara. Figure 3 highlights the enhanced brightness visible in the thin winged structures arising from the coating of the aluminum powder onto the surface of the maple samara. In comparison to the untreated sample (Figure 2), the surfaces of the wing portion of the sample are now much closer in grayscale value to the signal arising from the seed. This normalization of grayscale within the dataset increases the efficacy of downstream analysis and conversion of the imaging data into a volumetric model.

While the aluminum spray did a notable job at improving the signal from the maple samara wing, we also tested a very common micro-CT contrast agent, phosphotungstic acid (PTA). By immersing a maple samara in a PTA solution for a day, we investigated the binding of PTA to the structures in the sample to determine if this method produces a suitably enhanced signal from the wing. Figure 4 demonstrates the vast increase in signal within the maple samara datasets on the outer surfaces of the sample. In both the untreated (Figure 2) and aluminum coated (Figure 3) samples the seed is the brightest signal in each dataset. In examining the PTA treated sample, the seed is almost invisible as the signal arising from the exterior surfaces is much higher in intensity due to the presence of a thin layer of tungsten deposited electrostatically on the maple samara2.

For hydrated samples, chemical drying provides an option to rapidly dehydrate the samples as well as boost X-ray attenuation. While the maple samara is not a hydrated sample, we explored the effect of hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) via a chemical drying process3. As shown in Figure 5, it appears HMDS pre-treatment did slightly boost the signal arising from the wing. However, in comparison to the other treatment methods the effect appears to be more subdued and this suggests HMDS pre-treatment is not particularly beneficial for this sample type.

In addition to the changes in local signal intensity within the datasets, the tested treatment methods also produced visible changes to the maple samaras (Figure 6). From left to right we have the PTA treated, aluminum coated, and then the HMDS treated samples. The HMDS chemical drying process was particularly tough on the sample, causing the thin winged structure to tear in multiple locations which gives further evidence of the incompatibility of HMDS chemical drying for this sample type. Both the PTA and aluminum coated samples retained their general shapes, but some fine details are lost on the surface of the aluminum coated sample as the thickness of the aluminum coating obscures minute surface structures on the samara.

Using CTVox, we visually compared the definition captured for each sample in 3D space as shown in Figure 7. While each dataset contains a wealth of structural information, some clear observations arise from this direct comparison. As noted earlier, the cracking observed on the fragile HMDS dried sample is evident. The bright surface signal arising from the aluminum coating is also particularly striking compared to the other samples but the overall loss of fine structural details, especially when compared to the PTA treated sample, likely means the aluminum coating is not a great match for this project as well. If the maple samara had fewer fine structures present on the surface, the aluminum coating treatment method would be particularly suitable as a low-cost and fast method for boosting signal on lightly attenuating surfaces. Among the four, the PTA treated sample is the clear winner in this group where we observe both a significant increase in surface brightness in the rendered dataset while also maintaining a high fidelity of the thin surface details. As such, we utilized the PTA treated dataset for our subsequent modelling steps aimed at producing a volumetric model of a maple samara suitable for computational fluid dynamics and digital modelling.

To produce a clean volumetric model of our maple samara dataset for downstream analysis, we imported the voxel-based dataset into Simpleware software with the CAD add-on module to convert our dataset into a model using the vast meshing tools available in the program. After a global segmentation of our imaging data, some fine holes remained even for the PTA treated dataset. To clear up these holes, a morphological closing function of 50 pixels strength was applied to the dataset in Simpleware. The two models were then overlaid upon one another to highlight where differences were observed, as shown in Figure 8. All the red signal is the result achieved with our global threshold value while the green regions are the patches that were applied to the model via the morphological closing operation. After being satisfied with the overall shape of the model from the conversion and cleanup process, Simpleware also allows us to fine-tune the mesh used to define the features of the model by re-meshing the dataset to reduce the total number of triangles used in the model while still maintaining the fine details captured with our high-resolution imaging.

Finally, we produced photorealistic rendered images of the model arising from our PTA treated maple samara with Maverick Indie, as shown in Figures 1 and 7.

Conclusion

Micro-CT is a versatile technique which can image almost any sample type that both fits within the instrument and allows for X-ray energy to pass through without full attenuation. In many cases, very low-density samples may be problematic for imaging as, even at the minimum X-ray power settings of the instrument, the sample may fail to attenuate enough X-ray energy to provide contrast from background air intensity. This article explored three different common treatment steps that facilitate the increase of X-ray attenuation in micro-CT imaging. Ultimately, treatment with phosphotungstic acid proved to be the most effective technique from this group for our maple samara sample. Finally, we converted our image stack into a STL model suitable for downstream finite element analysis and modelling using Simpleware by Synopsis.

We hope you find this Image of the Month article informative and encourage you to subscribe to our newsletter and social media channels in preparation for the continuation of our Image of the Month series next month.

Scan Specifications

| Sample | Maple Samara |

| Voltage (kV) | 40 |

| Current (µA) | 100 |

| Filter | None |

| Voxel Size (µm) | 15 |

| Rotation Step (deg) | 0.3 |

| Exposure Time (ms) | 2215 |

| Rotation Extent (deg.) | 180 |

| Scan Time (HH:MM:SS) | 04:24:09 |

These scans were completed on our Bruker SkyScan 1273 instrument at the Micro Photonics Imaging Laboratory in Allentown, PA. Reconstructions were completed using NRecon 2.0 while visualization and volumetric inspection of the 2D and 3D results were completed using DataViewer and CTVox. The PTA treated maple samara dataset was converted to a STL volumetric model using Synopsys’ Simpleware software with the CAD add-on module (Synopsys, Inc., Mountain View, USA) before 3D rendering using Maverick Render Indie (Random Control, Madrid, Spain).

Would you like your work to be featured in our monthly newsletter? If so, please contact us by calling Seth Hogg at 610-366-7103 or emailing seth.hogg@microphotonics.com.

References

*Simpleware software (Synopsys, Inc., Mountain View, USA) enables you to comprehensively process 3D image data (MRI, CT, micro-CT, FIB-SEM…) and export models suitable for CAD, CAE and 3D printing. Use Simpleware software’s capabilities to visualize, analyze, and quantify your data, and to export models for design and simulation workflows. Simpleware™ is a trademark of Synopsys, Inc. in the U.S. and/or other countries.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samara_(fruit)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phosphotungstic_acid

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hexamethyldisiloxane